Meta-Practice:

Artistic Production as Promotion

BY TIM ROSEBOROUGH

When is a magazine placement a unique form of artistic gesture? What is revolutionary about a website presented as artwork? How does an artist's practice travel from the studio to the art world's consciousness, and can the artist help facilitate that journey?

These questions can be answered when examined through the prism of "Meta-Practice:" an ages-old but little-remarked-upon strategy with specific social and aesthetic values and great potential to communicate the power of contemporary art practice.

Meta-practice is "after-practice:" the set of processes (and products) through which an artist's practice are communicated to and disseminated throughout the art world and general society.

That the word "practice" is part of my coinage stems from my belief that artists can consider meta-practice as a branch, if not an integral component, of their activities, and that it is possible to discern artistic intent in these endeavors, extending the borders of art making.

On a fundamental level, meta-practice involves promotional activities including exhibition, marketing, public relations, advertising and other pursuits necessary to attract attention to an artist's practice. What distinguishes meta-practice from standard promotion is that the artist's distinctive intentions, designs and methods can be integrated as formal and aesthetic strategies, turning the means of attracting attention into its own aesthetic pursuit.

FROM PRODUCER TO PROMOTER

Without regard to the degree of assistance employed in the realization of an artwork, the traditional and predominant role of the artist is as "producer." The traditional expectation is that the "studio," or place of production (whatever form it may take), serves as the majority of the artist's concern.

Traditionally, commercial galleries, independent and institutional curators and similar entities plan, coordinate and execute the presentation of an artist's practice to the art audience and larger community. Later, art writers and critics may enrich the conversation through reviews and discussions in magazines, journals and other art-related publications.

In addition to artists who receive these promotional services through commercial or institutional channels, there are those who, by circumstance, necessity or ambition, hope to replicate, critique or augment this support through their own efforts.

These artists are engaging in meta-practice: activities, production and strategies in which an artist hopes to gain access to -- and attention from -- the loosely connected amalgam of curators, collectors, academics, critics, dealers, museums, publications, galleries and exhibition spaces we call the "art world."

FURTHER DEFINING META-PRACTICE

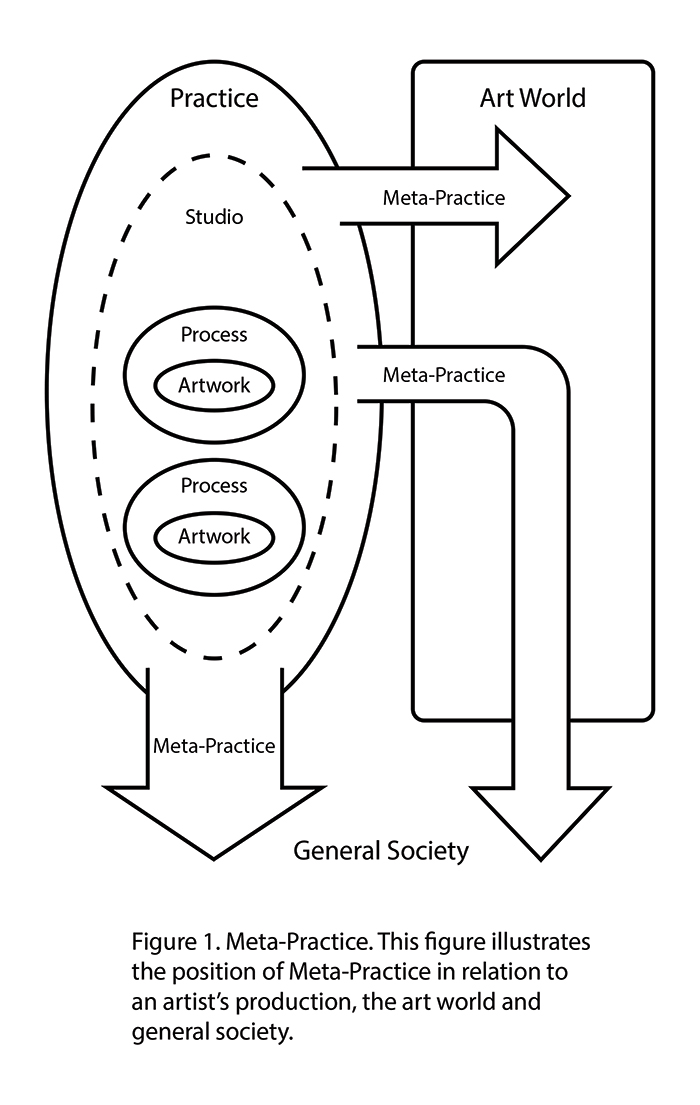

The definition of meta-practice is best illustrated by the diagram I have constructed (see Figure 1) that contextualizes an artist's practice in relation to the art world and broader society.

Let us imagine a closed area that represents one ARTWORK (of any medium) by an artist. Surrounding that is another closed area that represents the PROCESS or set of processes of which the artwork is the result. This process-artwork combination is surrounded by a larger closed area that represents the entirety of the artist's PRACTICE (which includes the artist’s physical STUDIO). The practice consists of as many process-artwork couplings as is in the artist's oeuvre. The META-PRACTICE is the set of processes and production by which the results of the artist's practice are communicated to the ART WORLD and GENERAL SOCIETY, which envelops the entirety of this grouping.

The latter half of the 20th century saw a rising artistic preoccupation with highlighting the processes that result in a work of art, often to the extent that the attention to a process eclipsed the concern with its results. Conceptualism in the late 1960s succeeded in dispensing with the "object" altogether, prioritizing ideas over materiality.[1] The 1970s witnessed performance and video exploring the aesthetic possibilities in the recognition of the body and the temporal. Developments in the 1990s saw a further expansion, as artists initiated "situations" from participation and social interaction models.[2] Meta-practice is one logical offshoot in the development of the progressive arts, capable of consolidating, refining and enhancing these earlier innovations, and continuing to break down the division between "practice" and "life."

META-PRACTICE IN PRACTICE

A fresh interpretation of well-worn (western) art history reveals how many celebrated artists engaged in meta-practice to help their work reach a sympathetic audience, especially at the beginning of their careers. I will briefly highlight a number of historical examples as a way of organizing these activities under my definition of meta-practice.

Meta-practice as I have defined it can be witnessed in:

· Ed Ruscha's print publications, including "Twenty Six Gasoline Stations" (1963) and "Every Building on the Sunset Strip" (1966) as well as his self-published magazine advertisement, "Ruscha Says Goodbye to College Joys" (Artforum, January 1967);[3]

· On Kawara's "I Got Up At" (1968-1979) series, in which he sent a concept-based series of postcards to art world contacts from around the globe;[4]

· Dan Graham's art pieces, placed in magazines such as "Homes For America" (Arts Magazine, 1966-1967) and "Figurative" (Harper's Bazaar Magazine, March, 1968);[5]

· Chris Burden's television ad placements during late night television, such as "Through The Night Softly" (1973) and "Chris Burden Promo" (1976) during the "Saturday Night Live" television program;[6]

· Jenny Holzer's "Truisms" (1977-1979), anonymous posters pasted on buildings, walls and fences in and around New York City;

· Jeff Koons' placement of advertisements in Artforum, Art, Art In America and Flash Art magazines for his 1988 Banality exhibition;[7]

· Damien Hirst and the "Young British Artists'" organization of the "Freeze" (1988) and "Modern Medicine" (1990) exhibitions in London;[8]

· Marilyn Minter's purchase of television time to air her piece, "100 Food Porn," (1990) in conjunction with a gallery show;[9]

· Takashi Murakami's branded lines of merchandise and toys, among others.[10]

· In addition, artists whose practices can fall under the rubric of "street art" or "graffiti art" are often engaged with meta-practice. Examples include:

· Keith Haring's early-1980s subway chalk drawings and opening of his "Pop-Shop" (1986);[11]

· Jean-Michel Basquiat's "Samo" graffiti (1977-1980) in New York City’s SOHO neighborhood;[12]

· Shepard Fairey's worldwide "obey" sticker and graffiti campaign;[13]

· Barry McGhee's graffiti drawings in the San Francisco area[14] and

· Banksy's stencil graffiti campaigns in England and across the globe.[15]

Each of the artists noted above maintains a unique relationship to the art world. Their reputations lie between poles of admiration and revulsion, fame and notoriety, celebration and disregard. In each case, the artists made a conscious effort to engage in meta-practice-related strategies: activities and art works that serve as a bridge between "production" and "promotion," bringing their artwork and ideas out of the place of production and into the art world and beyond.

"Street" artists such as Banksy have developed practices that circumvent the standing art world structures altogether. The Internet is an important facilitator of dissemination and documentation for street artists' often-ephemeral work, and the broader society becomes the space of production, promotion and exhibition all at once.

It is not always necessary that the artist's practice and its results gain currency in the art world for them to do so in general society, as artists such as Thomas Kinkade have demonstrated.[16] On a similar note, practices such as those of Kinkade, Romero Britto[17] and Dale Chihuly[18] include the channel of sales, circumventing the traditional gallery structures of the mainstream art world to achieve sales as part of their meta-practice. As exemplified by these artists, sales can be integral to an artist's meta-practice. Still, sales are not necessary for meta-practice to be effective.

EVOLVING MODELS IN CULTURAL PROMOTION AND DISTRIBUTION

To place meta-practice in a broader context, it warrants noting that other areas of cultural production have moved into more artist-initiated modes of communication and dissemination.

Whereas works that emerged from the self-publishing arena of the book industry were once scrutinized as being of suspect quality and dismissed as "vanity" publications, a new wave of writers have utilized advancing technologies to publish well-regarded books that reached an enthusiastic audience with fewer of the promotional and legitimizing functions of the publishing industry.[19]

Similarly, the mainstream music industry coexists with a long tradition of "do-it-yourself" or "indie" practices in which artists develop alternative networks of promotion and dissemination of their work. The music industry is witnessing a notable change in its business model from one in which major labels control all points in the production, promotion and distribution chain to a more fluid model in which individual and unsigned artists can reach vast audiences through their own efforts.[20]

The lesson to be learned from the evolution of other modes of cultural production is that radical changes are occurring not solely within the constrained realm of formal concerns, but in the broader aspects of how work can be communicated and distributed.

THE FUTURE OF META-PRACTICE

As we careen into the 21st century, I posit that for many artists, the lines between "producer" of artwork and "promoter" of artwork will continue to dissipate. The Internet's power lies in its ability to broadly and quickly distribute ideas and images. Its potential for altering how artwork is presented, promoted and valued is still in its nascent phases. Artists whose main medium is the Internet have the option to create artworks whose primary manifestation is a public website. By most measures, this means that the work is available both instantaneously and globally. In addition, web-based artworks are "expanded" art works in the sense that they can include links to further information about -- and other artworks by -- the artist. The networked, decentralized and widely accessible nature of the Internet has facilitated an environment in which a singular artwork is accessible to viewers in a manner that was not previously possible, collapsing the spaces of "exhibition" and "promotion."

In the physical (as opposed to virtual) world, the proliferation of the international art fair culture has spawned venues that complement the well-known art fairs by allowing artists to exhibit without the auspices of a commercial gallery. These "independent artist" fairs allow artists to replicate some of the exhibition and promotional functions of the mainstream commercial galleries, with the benefit that the artists are offered greater aesthetic control over how their work is presented to the public.[21]

Because meta-practice can involve engaging exhibition, media and communication platforms that are transactional businesses, artists who engage in meta-practice often make financial investments in the promotion and exhibition of the fruits of their practices. This includes, at times, purchasing advertising space or media time, procuring Internet addresses, renting or negotiating for exhibition space, or collaborating with exhibition spaces that expect that the artist will contribute financially to the costs of mounting and promoting the exhibition. In this way, meta-practice is linked with entrepreneurship, and I contend that all these activities are viable strategies within meta-practice: The artist devotes resources and energy not just to the production of art, but to providing a platform for the work to be witnessed and evaluated on his or her own artistic terms.

The field of art will continue to expand and evolve, to transgress borders, breaking old assumptions and questioning restrictions and taboos, formal, moral and normative alike. The space between production and promotion is a fertile soil for the outgrowth of a fascinating set of manifestations. Artists are free to explore the vast creative possibilities of articulating the fruit of their practices.

Meta-practice connects an artist's work to the world. The artistic gesture becomes more than a product: It is the blossom of a complex structure rooted in biography, place, circumstance, skill and strategy. The work that results from an art practice that integrates meta-practice will prove meaningful because consideration is given to the constellation of forces and factors that make it visible, present and, most importantly, alive.

NOTES

[1] Irving Sandler, introduction, in Art of the Postmodern Era: From the Late 1960s to the Early 1990s (New York, N.Y.: Harper & Row, 1998), 11-18.

[2] Claire Bishop, "The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents," Artforum International February 1, 2006, pg. 179.

[3] Neal David Benezra, Kerry Brougher, and Phyllis D. Rosenzweig, Ed Ruscha (Washington, DC: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, 2000), 178-179.

[4] Olle Granath et al., On Kawara: Continuity / Discontinuity 1963-1979 (Stockholm: Moderna Museet, 1980), 105-109.

[5] Bennett Simpson and Chrissie Iles, Dan Graham: Beyond (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2009), 128-129, 134.

[6] Donald Kuspit et al., Chris Burden: A Twenty Year Survey, ed. Anne Ayres and Paul Schimmel (Newport Beach, CA: Newport Harbor Art Museum, 1988), 156.

[7] Katy Siegel, Ingrid Sischy, and Eckhard Schneider, Jeff Koons, ed. Hans Werner. Holzwarth (Köln: Taschen, 2009), 253-257.

[8] Gregor Muir, Lucky Kunst: The Rise and Fall of Young British Art (London: Aurum, 2009), 18-19.

[9] Mary Heilmann et al., Marilyn Minter. (New York: Gregory R. Miller &, 2010), 29-35.

[10] Scott Rothkopf, "Takashi Murakami: Company Man," in © Murakami (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007), 128-159.

[11] Alexandra Kolossa, Keith Haring, 1958-1990: A Life for Art (Köln: Taschen, 2004), 47.

[12] Leonhard Emmerling, Jean-Michel Basquiat (Köln: Taschen, 2006), 11-12.

[13] Jeffrey Deitch and Antonino D'Ambrosio, Mayday: The Art of Shepard Fairey (Berkeley, CA: Gingko Press, 2011), 13.

[14] Alex Baker et al., Barry McGee, ed. Lawrence Rinder (Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, 2012), 91-92.

[15] Will Ellsworth-Jones, Banksy: The Man behind the Wall (New York, NY: St Martin's Press, 2013), 66.

[16] Alexis L. Boylan, ed., Thomas Kinkade: The Artist in the Mall (Durham [N.C.: Duke University Press, 2011), 181-183.

[17] Alex Williams, "In Miami, Art Without Angst," New York Times, February 4, 2007, sec. 9.

[18] Gayle Clemans, "Highlights — and Low Points — of Chihuly Garden and Glass," The Seattle Times, May 20, 2012, Arts, n.p.

[19] Evan Hughes, "The Plot Thickens," Wired, April 2013, pg. 76.

[20] Jeffrey Leeds, "Independent Music on Move with Internet," New York Times, January 10, 2006.

[21] Events such as the long-running PooL art fair that occurs concurrently with the Armory New York and Art Basel Miami fairs, respectively, allow artists who are not represented by commercial galleries to exhibit their work in a proper art fair context.

Bibliography

Baker, Alex, Natasha Boas, Germano Celant, and Jeffrey Deitch. Barry McGee. Ed. Lawrence Rinder. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, 2012. Print.

Benezra, Neal David, Kerry Brougher, and Phyllis D. Rosenzweig. Ed Ruscha. Washington, DC: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, 2000. Print.

Bennett-Smith, Meredith. "'50 Shades of Grey': What Is the Appeal?" CSMonitor.com. Christian Science Monitor, 15 Mar. 2012. Web. 26 June 2013.

Bishop, Claire. "The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents." Artforum International 1 Feb. 2006: 178-83. Print.

Boylan, Alexis L., ed. Thomas Kinkade: The Artist in the Mall. Durham [N.C.: Duke UP, 2011.] Print.

Caillois, Roger. Man, Play, and Games. [London]: Thames and Hudson, 1962. Print.

Chihuly, Dale, and Timothy Anglin. Burgard. The Art of Dale Chihuly. San Francisco: Chronicle, 2008. Print.

Chu, Petra Ten-Doesschate. The Most Arrogant Man in France: Gustave Courbet and the Nineteenth-Century Media Culture. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2007. Print.

Clemans, Gayle. "Highlights — and Low Points — of Chihuly Garden and Glass." The Seattle Times. N.p., 20 May 2012. Web. 02 July 2013.

Deitch, Jeffrey, and Antonino D'Ambrosio. Mayday: The Art of Shepard Fairey. Berkeley, CA: Gingko, 2011. Print.

Ellsworth-Jones, Will. Banksy: The Man behind the Wall. New York, NY: St Martin's, 2013. Print.

Emmerling, Leonhard. Jean-Michel Basquiat: 1960-1988. Köln: Taschen, 2006. Print.

Granath, Olle, Felix Zdenek, R. H. Fuchs, and Keinosuke Murata. On Kawara: Continuity / Discontinuity 1963-1979. Stockholm: Moderna Museet, 1980. Print.

Heilmann, Mary, Matthew Higgs, Johanna Burton, and Sonia Campagnola. Marilyn Minter. New York: Gregory R. Miller &, 2010. Print.

Hughes, Evan. "The Plot Thickens." Wired Apr. 2013: 76-80. Print.

Kolossa, Alexandra. Keith Haring, 1958-1990: A Life for Art. Köln: Taschen, 2004. Print.

Kuspit, Donald, Tom Marioni, David A. Ross, and Howard Singerman. Chris Burden: A Twenty Year Survey. Ed. Anne Ayres and Paul Schimmel. Newport Beach, CA: Newport Harbor Art Museum, 1988. Print.

Leeds, Jeffrey. "Independent Music on Move with Internet." New York Times 10 Jan. 2006. Print.

Leeds, Jeffrey. "The Net is a Boon for Indie Labels." New York Times 27 Jan. 2005: E1 Print.

Madoff, Steven Henry, ed. Art School: (Propositions for the 21st Century). Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2009. Print.

Michels, Caroll. How to Survive and Prosper as an Artist: Selling Yourself without Selling Your Soul. New York: H. Holt, 1997. Print.

Muir, Gregor. Lucky Kunst: The Rise and Fall of Young British Art. London: Aurum, 2009. Print.

Rothkopf, Scott. "Takashi Murakami: Company Man." © Murakami. Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007. 128-59. Print.

Sandler, Irving. Introduction. Art of the Postmodern Era: From the Late 1960s to the Early 1990s. [New York [N.Y.]]: Harper & Row, 1998. Print.

Schavemaker, Margriet, and Mischa Rakier, eds. Right about Now: Art & Theory since the 1990s. Amsterdam: Valiz, 2007. Print.

Siegel, Katy, Ingrid Sischy, and Eckhard Schneider. Jeff Koons. Ed. Hans Werner. Holzwarth. Köln: Taschen, 2009. Print.

Simpson, Bennett, and Chrissie Iles. Dan Graham: Beyond. Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2009. Print.

Sisario, Ben. "As Music Streaming Grows, Royalties Slow to a Trickle." New York Times 29 Jan. 2013: A3. Print.

Taylor, Paul. "The Art of P.R., and Vice Versa." New York Times 27 Oct. 1991: H1. Print.

Thompson, Donald N. The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. Print.

Thornton, Sarah. Seven Days in the Art World. New York: W.W. Norton, 2008. Print.

Trebay, Guy. "Sex, Art and Videotape." New York Times Magazine 13 Jun. 2004: A20. Print.

Williams, Alex. "In Miami, Art Without Angst." New York Times 4 Feb. 2007, Fashion & Style sec. 9: 1. Print.

© 2013 Tim Roseborough